The Contradictory Legacy of William Morris: Architect of the Arts and Crafts Movement

ByJohn B

The Contradictory Legacy of William Morris: Architect of the Arts and Crafts Movement

There are few Victorian figures more bewitchingly complex than William Morris. A poet, designer, entrepreneur, environmentalist, novelist, activist… and, rather thrillingly, a dreamer with calloused hands. Morris didn’t so much dabble in disciplines, as redefine them. Through founding the Arts and Crafts movement, he rewrote the visual language of domestic Britain and seeded the roots of modern design philosophy. Yet, within this brilliance lay a series of exquisite contradictions and unresolved tensions that make his legacy all the more human.

The Formation of a Revolutionary Mind

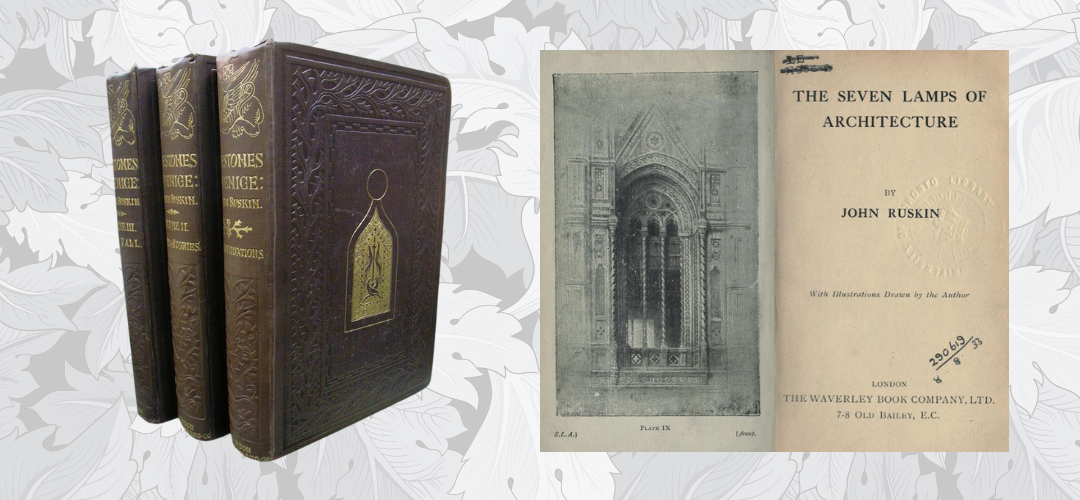

Our journey begins in the gothic halls of Oxford, where a young Morris, nominally training in theology, encountered Edward Burne-Jones, a meeting that sparked a lifelong friendship and creative kinship. It was here, in those dreaming spires, that Morris also discovered the radical writings of John Ruskin. Ruskin’s searing critiques of industrialism and his near-religious reverence for craftsmanship struck Morris like a bell. The Stones of Venice and The Seven Lamps of Architecture were his manifestos in disguise.

Edward Burne-Jones and John Ruskin

Edward Burne-Jones and John Ruskin The Stones of Venice and The Seven Lamps of Architecture

The Stones of Venice and The Seven Lamps of ArchitectureAlongside Ruskin came the impassioned moral commentaries of Charles Kingsley and Thomas Carlyle, and suddenly, Morris’s world was ablaze with ideas: art, justice, beauty… all intertwined. He and Burne-Jones abandoned the cloth for culture, trading sermons for stained glass and parish life for a “life in art.”

The Dream of Dante - Dante Gabriel Rossetti c.1871

The Dream of Dante - Dante Gabriel Rossetti c.1871Though Morris trained briefly in architecture under George Edmund Street, it was his encounter with the charismatic Dante Gabriel Rossetti that swayed him toward painting. Alas, canvas was never quite his medium, but in that failure, Morris discovered design.

Red House: Manifesto in Brick and Mortar

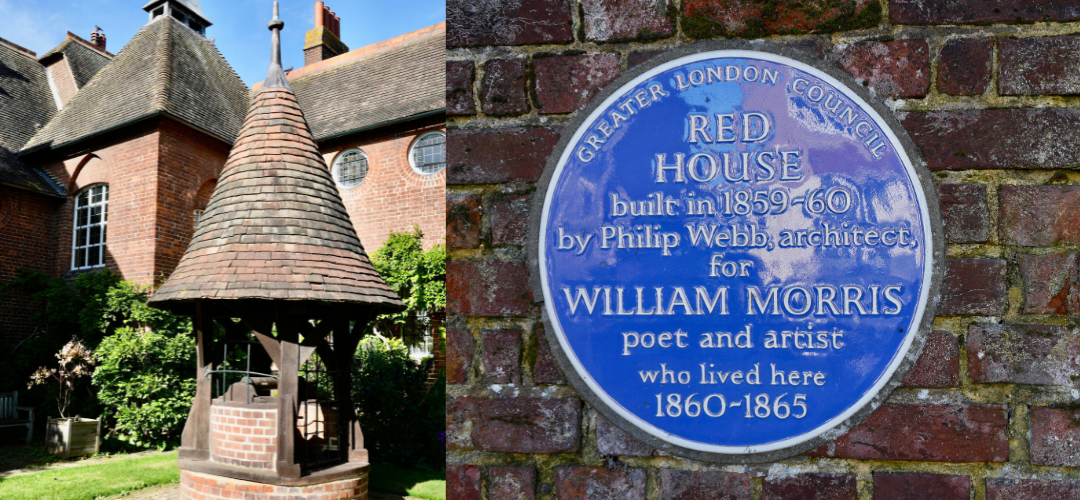

It was in the building of Red House (his family home in Kent, created with his dear friend Philip Webb), that Morris’s aesthetic philosophy bloomed. More than a mere dwelling; it was an idea in brick, a handcrafted hymn to medieval romance and domesticity. Built between 1859 and 1860, Red House wore its ideals on its gabled sleeves.

Gone were the classical proportions and symmetrical façades of polite architecture. Instead, Webb offered steep roofs, pointed arches, grand chimneys and a deep sense of integrity. It was British, bold, and breathtaking. The house embodied Morris’s belief that beauty should arise from purpose, and that domestic spaces could… indeed should, be poetic.

Inside, it became a living gallery. Murals, metalwork, embroidered wall hangings, stained glass, each lovingly crafted by Morris and his Pre-Raphaelite circle. Red House was a sanctuary of experimentation; a living organism where ideas became form.

Red House by William Morris and Philip Webb

Red House by William Morris and Philip WebbThe Paradox of Commercial Success

In 1861, Morris co-founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., bringing together a cast of Pre-Raphaelite luminaries with the lofty ambition of returning artistry to everyday life. The company aimed to make honest, beautiful things - medieval in spirit, thoroughly moral in execution.

But herein lay the rub: handcraft is labour-intensive and therefore expensive. The company, in its pursuit of ethical, joy-giving design, inadvertently priced itself far beyond the reach of the working classes it claimed to champion. The much-admired Sussex chair… humble, honest, and beautifully made, became a runaway success, but its reach remained limited to the affluent.

Morris, ever self-aware, acknowledged the irony with a weary sigh. He was “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich” while preaching fellowship and equality. A contradiction that gnawed at him for life.

The Sussex Chair

The Sussex ChairThe Socialist Dilemma: Craft versus Machine

Morris's politics grew bolder with age. He joined the Social Democratic Federation, then the Socialist League, passionately advocating for economic justice. But he could never quite reconcile his political ideals with his aesthetic purism. Machinery, so often the enemy, could have helped democratise design. Yet Morris remained loyal to the craftsman’s touch, even when it clashed with his egalitarian dream.

He envisioned a society where creative labour nourished the soul… a fraternal utopia drawn not from theory but from tapestry and wood. But he was, at heart, a 19th-century romantic caught in a very 20th-century problem: the tension between beauty and access, vision and viability.

Larkspur by William Morris

Larkspur by William MorrisEnvironmental Pioneer and Cultural Critic

His criticisms of industrialisation were not limited to factory floors. Morris railed against environmental degradation and the erasure of beauty in urban life. In 1877, he co-founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, becoming one of the earliest voices for conservation. “Hatred of modern civilisation” was not a throwaway phrase, but the compass of his life's work.

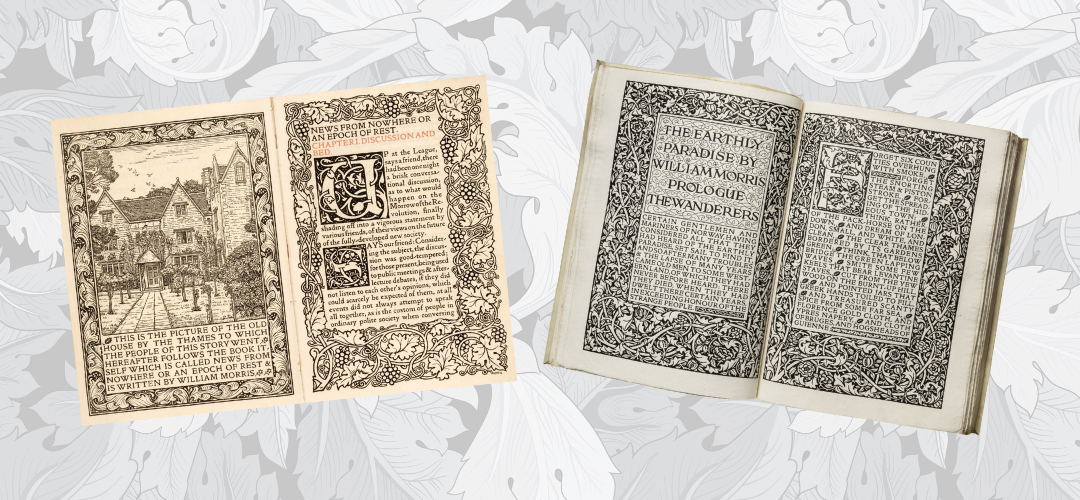

Through books like The Earthly Paradise and News from Nowhere, he offered shimmering visions of better worlds: societies in harmony with nature, with one another, with craft. These were not escapist fantasies but blueprints of resistance — ideas that seeded future generations of activists, artists, and idealists.

The Earthly Paradise and News from Nowhere by William Morris

The Earthly Paradise and News from Nowhere by William MorrisThe Enduring Contradiction

The contradictions at the heart of William Morris's life were not failures, but signposts. He lived in the friction between idealism and action, between the medieval and the modern. His refusal to compromise, while costly, ensured his ideas endured.

Morris showed us that design is not just about objects, but about ethics, people, and place. He left us not answers, but a set of questions that feel as urgent now as they did then. How do we design for people, not profit? How do we preserve beauty in a world obsessed with speed? And can art, in the end, help us build something better?

He didn’t solve it. But he started the conversation… and that, perhaps, is the most revolutionary act of all.