When it comes to style then Professor Andrew Groves is one of those people who has been there and designed the t-shirt. One of my favourite people to sit down and share a pint with, having written a number of books he’s a fountain of knowledge when it comes to all things British menswear related. Also a leading authority on fashion design he is the founder of the amazing Westminster Menswear Archive. An essential resource for academics, designers, and industry professionals looking for insight and inspiration beyond the predictable parameters of Pinterest can get their hands on some truly amazing garments. All of which make the perfect credentials for us to interview him for WLYL.

"British style isn’t about cohesion or polish, its contradiction, confidence, and class tension. The refusal to dress for the weather. It’s about how people push against the expected and find style in the everyday."

Purple Mountain Observatory Obsidian Jacket, C.P. Company Orange Crewneck, Hanes T-shirt, Nudie Grim Tim Dry Japan selvedge jeans, Burlington argyle socks, Mephisto Rainbow in chestnut.

Purple Mountain Observatory Obsidian Jacket, C.P. Company Orange Crewneck, Hanes T-shirt, Nudie Grim Tim Dry Japan selvedge jeans, Burlington argyle socks, Mephisto Rainbow in chestnut.So Andrew, talk us through what you’re wearing today mate…

It looked like rain, so I’ve got a coat on. It’s a Purple Mountain Observatory Obsidian Jacket – heat-reactive, shifts colour as the temperature changes. Underneath, a C.P. Company orange crewneck in French terry, Hanes T-shirt, Nudie Grim Tim Dry Japan selvedge jeans, Burlington argyle socks, and Mephisto Rainbow in chestnut. Function, fabric, and legacy; all doing their job.

When did you first become aware of style?

1976. I was about eight. We were at some countryside fair in the middle of nowhere, and I saw a bloke in a Sex Pistols “God Save the Queen” T-shirt with a pierced ear. It felt dangerous, like clothing could start a riot. That stuck with me. A few years later, Grease came out and I was obsessed with the T-Birds. Both showed how style could shape identity.

Vivienne Westwood (British, born 1941) and Malcolm McLaren (British, 1946–2010). “God Save the Queen” T-Shirt, 1977.

Vivienne Westwood (British, born 1941) and Malcolm McLaren (British, 1946–2010). “God Save the Queen” T-Shirt, 1977.If we created a timeline of your personal style, what would it look like?

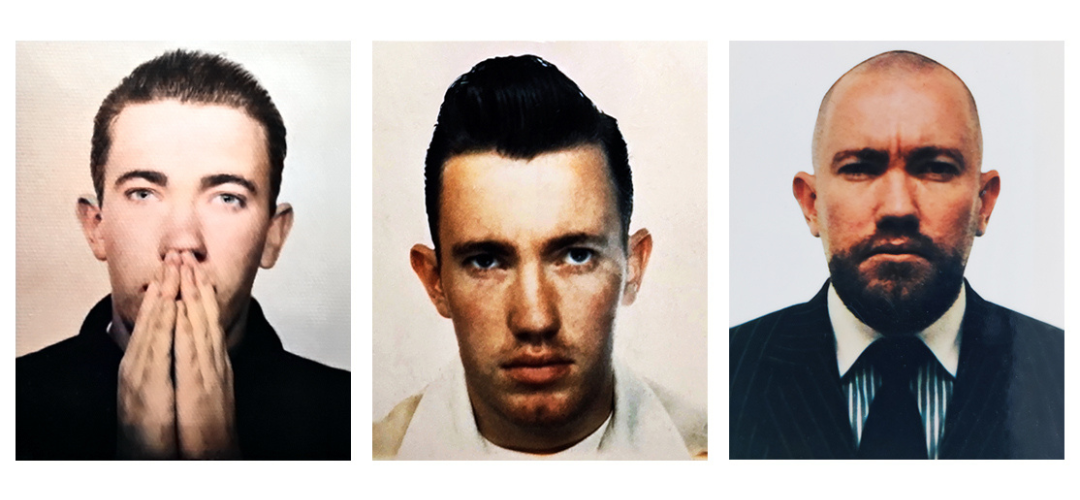

Skinhead, Mod, Rocker, Arthouse Pseud, Greaser, Casual, Freak, Raver, Dresser. Pretty much every subculture going. I was even suited up on Savile Row in the ’90s. So when it now comes to my work and research, I’ve lived every subculture and look from the inside. I think that brings a different kind of knowledge to my work. I understand menswear from actually wearing and living it, rather than just from books.

Andrew Groves Through the Years

Andrew Groves Through the YearsIs it true you used to make clothes in a sex shop?

Yes. While I was studying at St Martins, I worked in a sex shop making leather gear. It was piece work; the more you made, the more you earned. I had the choice of sewing leather jeans or chaps, but chaps were quicker: no back, no zip, so better money. The stories I could tell you from there, but at the end of the day, they were still clothes.

At the same timeI’d just enrolled at St Martins on the MA Fashion course. My tutor, the legendary Louise Wilson, was fascinated by me working in a sex shop, she was always asking me about it. Ironically, the people I worked with in the sex shop thought fashion school sounded far stranger than anything we were selling.

Discover more about Louise Wilson

You were part of London’s 1990s couture scene. How did that happen, and how glamorous was it really?

I wouldn’t call it couture; it was mainly left over scraps of fabric and shrink wrap. It was not remotely glamorous. It was blood, sweat, no sleep, and a squatted studio space. I’d met Lee McQueen in a pub in Soho through a mutual friend. Ten minutes later we were chucked out for smoking a joint. But as soon as he found out I could sew, he roped me into helping on collections. It was chaotic and intense, a group of mates building something radical with whatever we had to hand. But looking back now it’s surreal to think that things I developed then, like the swallow print, have become McQueen house codes.

Why does the ’90s still cast such a long shadow over fashion?

Because it was the last time fashion still felt dangerous. People took real risks. They weren’t polishing a legacy or chasing a brand identity, they were just making work that felt real. The rules weren’t fixed, and even if they were, no one followed them.

Designers didn’t talk about content or storytelling, they just put their heads down and made something that could blow your mind. That’s why the ’90s still casts such a long shadow. Not because people want to copy it, but because they want to feel that edge again, the moment when fashion wasn’t about strategy, it was about shock and subversion.

Westminister Menswear Archive

Westminister Menswear ArchiveTell us how the Westminster Menswear Archive came about.

The Archive was founded to address a clear gap: there was no UK collection dedicated solely to menswear. Despite its cultural and commercial significance, menswear is consistently sidelined, treated as secondary or as an adjunct to womenswear collections

I set out to change that by building an archive that took menswear seriously. Not as a trend or spectacle, but as a discipline. We collect everything from military uniforms and industrial workwear to tailoring, streetwear, and sportswear, garments designed to be worn, not just looked at.

We now have over 3,000 pieces, and the archive supports students, researchers, curators, and global brands. At its core, it’s about understanding how menswear works, materially, culturally, and historically, and using that to inform both new design and new thinking.

The Westminister Menswear Archive

Why is menswear still overlooked in fashion?

It isn’t when it comes to sales or cultural influence. But academically and curatorially, it still gets sidelined. Most institutions focus on fashion as spectacle; extraordinary, extravagant, and almost always womenswear.

Menswear works differently. It’s quieter and it evolves through repetition, not constant reinvention. That doesn’t necessarily generate headlines, but it does tell you far more about class, identity, and power than most runway shows ever will.

Some say the Archive reflects your personal wardrobe. True?

Out of more than 3,000 garments in the archive, there’s only two pieces that I also own myself. It was never set up to reflect my own taste or preferences. From the beginning, I made a deliberate choice not to curate around a single aesthetic or point of view, so there are plenty of garments in the collection I wouldn’t wear, and that’s exactly the point.

It's designed to challenge assumptions and broaden perspectives. It brings together a wide range of garments across different contexts: military, tailoring, streetwear, workwear. The goal is to support a more inclusive and critical understanding of what menswear is, and what it can be.

You’ve been visiting archives in New York – what did you see?

I spent time at the PVH Archive looking at the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger collections, two very different takes on brand heritage. They also showed me their designer inspiration archive. There was a New York fireman’s jacket that likely influenced Raf Simons' version for Calvin Klein. It was fascinating to see that direct line of reference, how a piece of functional uniform ended up reimagined on the runway.

I also visited teaching collections at FIT and Parsons, both were fantastic, but menswear made up maybe 10% of what they hold. It confirmed to me there’s real potential for a dedicated menswear archive in New York.

What are your current favourites from the Westminster Menswear Archive?

Usually whatever’s just arrived. We’ve just acquired an Aitor Throup skull bag, a pair of Electricity North West coveralls, a 66°North parka, and the Lidl by Lidl coat and tambourine. That mix, avant-garde design, industrial PPE, high-performance outerwear, and supermarket merch, says more about where fashion is right now than most exhibitions or runway shows.

Check out our 66 Degrees North Collection

Lidl by Lidl coat and tambourine

Lidl by Lidl coat and tambourineYou’re an expert on Massimo Osti. Which of his works stands out to you?

I’ve been researching his early work, pieces he did for Anna Gobbo, and his first Chester Perry prints. What defines his genius is that it wasn’t about aesthetics. It was systemic. He once said, “I was born Osti, so I am obstinate.” That resistance to compromise shaped everything. He designed entire systems, not just garments.

You're also a Man City fan – excited for the new season?

Always. Doesn’t matter what happens on the pitch. There’s always a new coat to wear and old mates to see!

Who’s your number one style icon?

Peter Saville. Not for what he wears, but for how he understands uniform, image, and cultural code. That’s real style, it's not just about appearance, but about how meaning gets constructed. He’s never followed the system; he’s always reshaped it.