Widely regarded as one of London’s most innovative fashion designers, since graduating from Central St Martin’s Shelley Fox has gone on to have her work both sold and exhibited all around the world. Now a leading design academic, she kindly took time out between moving continents to have a chat with British Attire about life in New York, rooting around Nick Cave’s archive and the surprisingly inspirational impact of mice.

Hi Shelley, first things first, can you talk us through what you’re wearing today?

I’m wearing my staple uniform of sorts – deep navy Uniqlo menswear shirt, sleeves always rolled up (and when I find the right shirt I buy five! As they get worn out, they get relegated to DIY and gardening shirts). Deep navy Comme des Garcons oversized, long gathered skirt with white Adidas Originals Superstar 2 – socks not showing. I used to wear heels all day everyday, until I had spinal surgery 5 years ago in 2020. I still have the heeled shoes / boots but I think surgery and Covid changed that way of wearing my clothes. Some of my outfits absolutely need heels, and they haven’t been worn for a while, but my uniform has changed in a way.

When did you first become aware of style?

Through music essentially, which was always being played in the family house growing up. My parents' music was varied, from my Dad’s obsession with Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, to my Mum’s which was The Beatles, Little Richard, all things rock n roll and particularly Motown artists. I wasn’t allowed out as a kid at the weekend until I had helped my mum with the housework, (they both worked full time) and so I would ask to have music playing loudly as it made it more enjoyable, and I got through the housework quicker... and then I could go out with my mates. I still clean the house like this today – I have to have music playing loudly. After that it was really going to gigs and reading The Face magazine which was really more focused on music in the very early 80s, hence the style. Also, iD magazine. I think that, and photographs of my Nanna in the 1930s – she made all her own clothes and was spectacularly stylish. I remember naively asking her in the 80s if I could have all her clothes and shoes from that period and I was mortified that she didn’t have them anymore... she had worn them until they fell apart.

You graduated from St Martins in 1996 where your final collection was instantly snapped up by Liberty’s, that must have been a pretty exciting time to be there. What was it like back then and who were your contemporaries?

Central St Martins College of Art

I was offered a knitwear job in Italy after two weeks of our CSM London Fashion Week graduation show with a company that did all the knitwear for Gaultier and Hugo Boss. I went to Italy for a week for a try out but I knew instantly it wasn’t going to work, so came back and met with the head buyer of Liberty. I was so naïve, but I think to some degree it was helpful because you had to push yourself forward and just ask people for help and make things happen even if you didn’t know what you were doing – you just learnt very quickly. One of the main things back then was that studios in London were inexpensive and you could take a lot more creative risks with your work. Everything felt possible and although the competition was intense, there was a big international focus on London designers at that time. My contemporaries were designers such as Andrew Groves, Vexed Generation, Boudicca, Jessica Ogden, Hussein Chalayan… there were so many…

Liberty London - Read the Heritage Story

Read our Thread on Andrew Groves

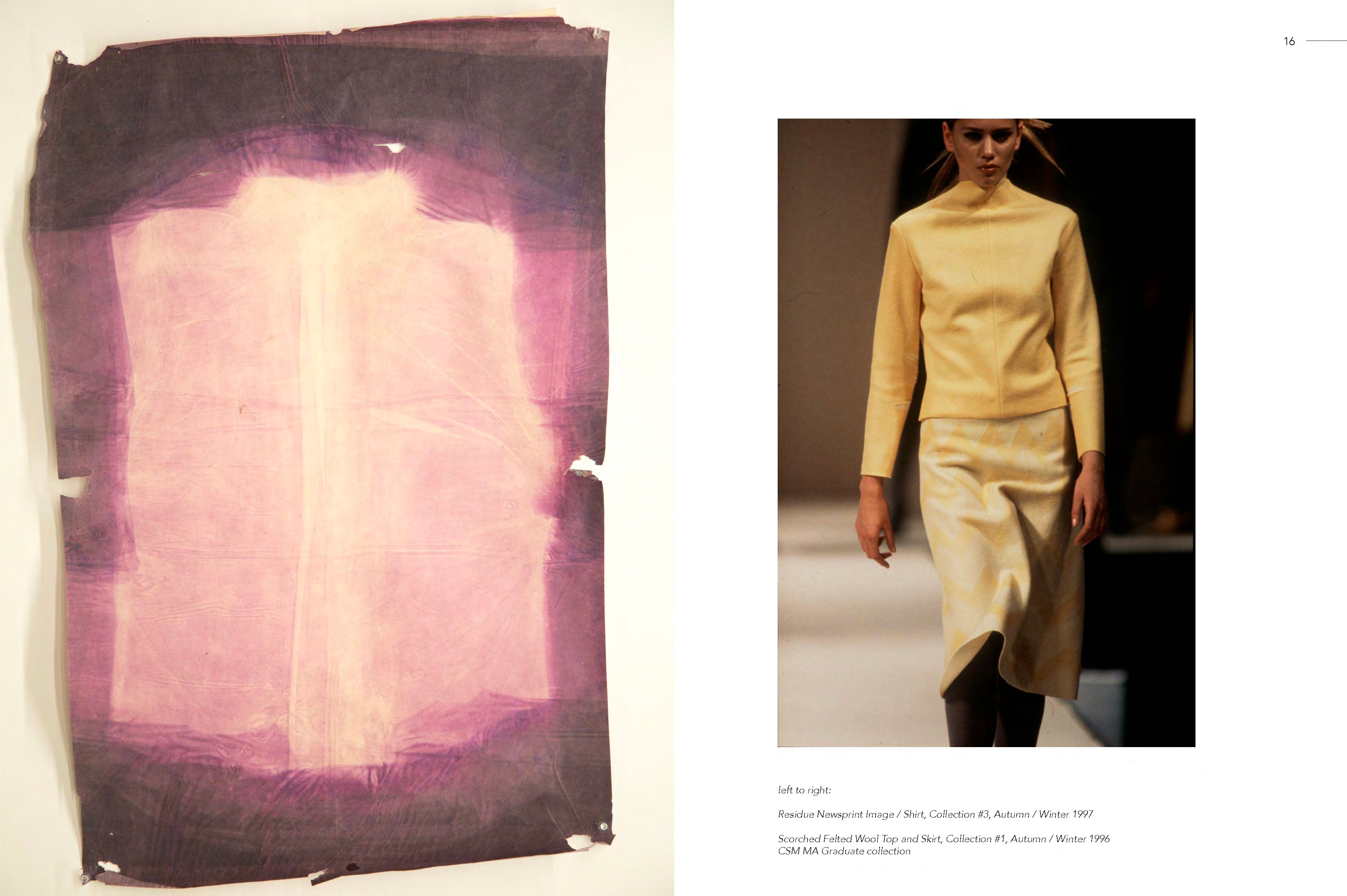

Left to right:

Residue Newsprint image / Shirt, Collection #3, Autumn / Winter 1997

Scorched Felted Wool Top and Skirt, Collection #1, Autumn / Winter 1996

Left to right:

Residue Newsprint image / Shirt, Collection #3, Autumn / Winter 1997

Scorched Felted Wool Top and Skirt, Collection #1, Autumn / Winter 1996Looking back, the nineties now feels like a golden era for fashion and culture, how does that decade make you feel?

That’s an interesting question because I am conscious not to feel nostalgic for that period, especially now working with young students, but it was very special – you felt like you could do so much on very little money, take risks and do interesting collaborations across all creative disciplines – it all felt wide open – fashion curation and the culture of fashion had found a new platform and audience. The exhibitions that my work participated in were always folded naturally into my practice from the beginning. By collaborating with curators, I found new possibilities in both the presentation and communication of the work to a wider global audience. I have the British Council and the Design Council to thank, as they funded a lot of these international travelling exhibitions. In part, the explanation around these funding mechanisms is an important factor to consider with regards to the economic landscape in London in the early 90s and onwards. It's key to understanding how artists and designers could work and survive, by offering low cost art school education, low studio rents, and support from cultural institutions who promoted British art and design at an international level. This all resulted in a prominent surge of collaborative creativity with a ‘nothing to lose’ attitude, where artists and designers became entrepreneurial risk-takers who put themselves on the global map of creative influence. Curators such as Andrew Bolton, Judith Clark, Amy de la Haye and so many others practice grew out of this time, and they broke so many rules within curation, creating and reaching new audiences – they really cared about the culture of fashion and the designers they worked with.

My work was never designed specifically for the exhibitions; but instead curators were drawn to the themes inherent within the work itself which brought new perspectives to contemporary fashion culture and the role of research. Examples included Braille and Moon Language (Royal National Institute of the Blind), Morse Code, Bletchley Park (the top-secret home of British World War Two Codebreakers and Alan Turing), 19th century bandaging techniques (The Wellcome Trust Library), lost or discarded photographs in flea markets, historical dolls (Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green), found diaries, and MRI scans of my own body – all seemingly at odds with developing a body of work around clothing, but these were the subjects that appealed to my design sensibility.

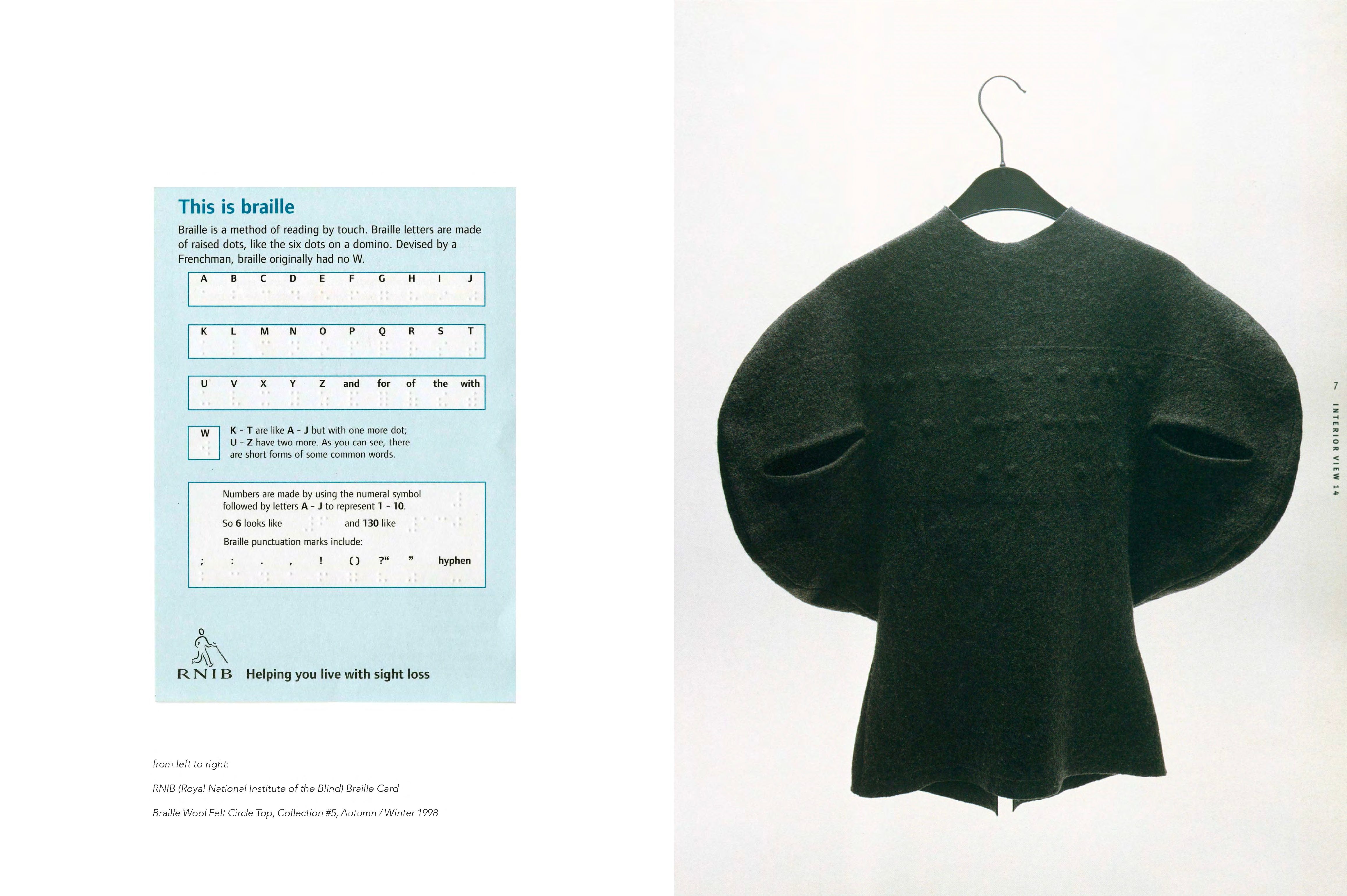

Left to right:

RNIB (Royal National institute of the Blind) Braille Card

Braille Wool Felt Circle Top, Collection #5, Autumn / Winter 1998

Left to right:

RNIB (Royal National institute of the Blind) Braille Card

Braille Wool Felt Circle Top, Collection #5, Autumn / Winter 1998As a designer you’ve earned a reputation for innovative fabrics and treating them with unique methods such as laser beams or sound waves.

Having trained in both BA Textiles Design and MA Fashion Design I was recognised for developing many of my own fabrications, cultivating my design identity from an early point. The fabrications were developed in the studio and, sometimes purposely, impossible to duplicate, enhancing the notion that ‘no two pieces are ever the same’. When you are physically making/designing the fabrics, the actual garment is forming in your mind – you literally see it unfold in front of you. You are responding to the real thing – the fabric - not a drawing. When you work like that, you know instinctively when it is right, when it is finished and what it will become. It is not a process you can handover to someone else but also, it’s the thing I love doing the most. Ruination is a word that best describes many aspects of my work and its aesthetic, where fabrics are blow-torched, scarred, smashed, scorched, laser burnt, imprinted, disintegrated and all play into a particular narrative producing a fragility in both visual and conceptual terms. Examples of these materials included Scorched Felt Wool, Burnt Elastoplast & Bandaging, Blow Torched Sequins, Spray Painted Felt, Dripping Wax Twinsets, Scarred Felt, and Smashed Beads.

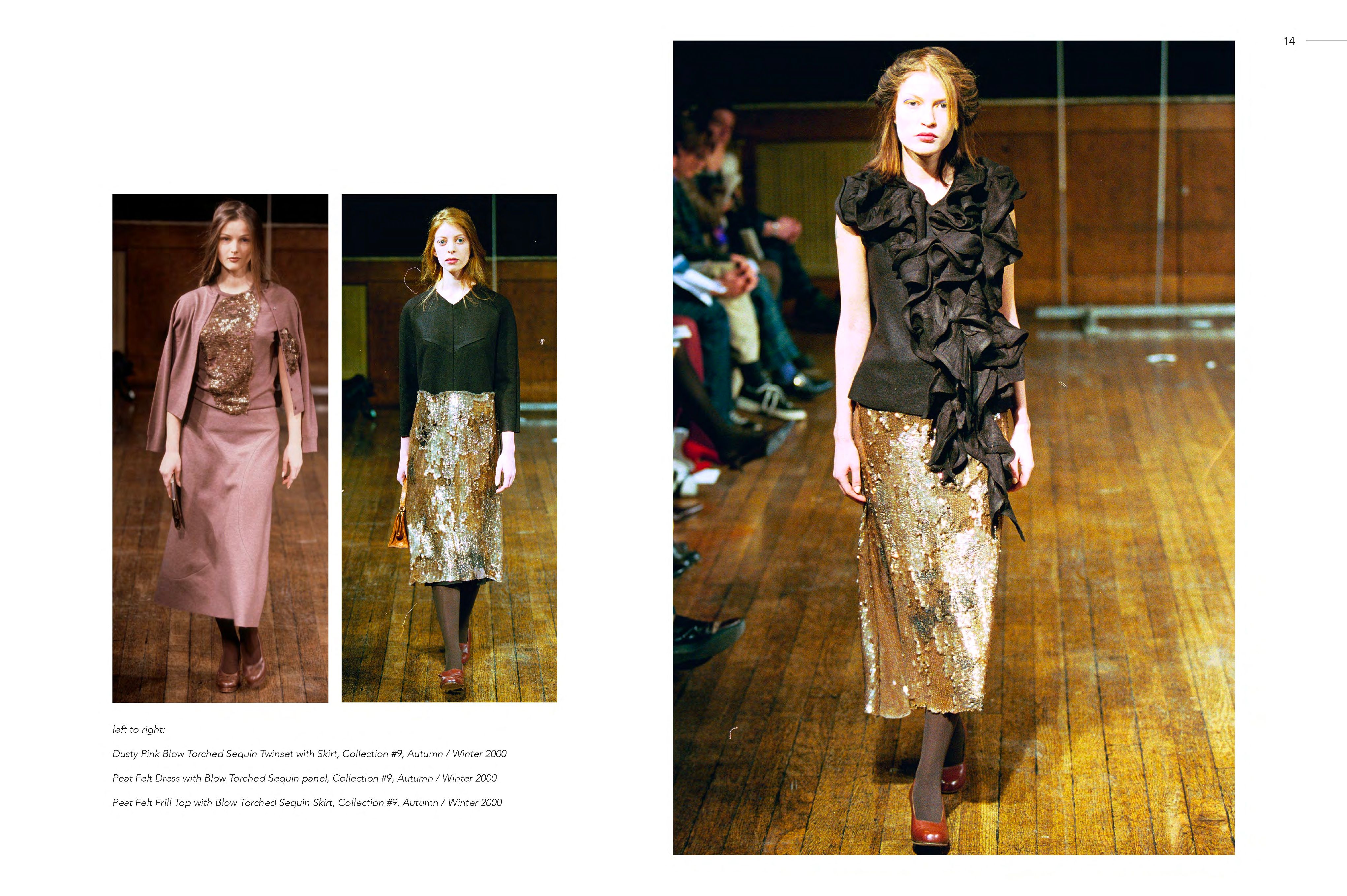

Left to right:

Dusty Pink Blow Torched Sequin Twinset with Skirt, Collection #9, Autumn / Winter 2000

Peat Felt Dress with Blow Torched Sequin panel, Collection #9, Autumn / Winter 2000

Peat Felt Frill Top with Blow Torched Sequin Skirt. Collection #9. Autumn / Winter 2000

Left to right:

Dusty Pink Blow Torched Sequin Twinset with Skirt, Collection #9, Autumn / Winter 2000

Peat Felt Dress with Blow Torched Sequin panel, Collection #9, Autumn / Winter 2000

Peat Felt Frill Top with Blow Torched Sequin Skirt. Collection #9. Autumn / Winter 2000Your work has appeared in lots of prestigious and award winning exhibitions around the world, which ones have you been most proud to be involved in and why?

I think it has to be the ‘Fashion at Belsay’ exhibition in 2004 which proved to be both personally rewarding, as well as challenging - being the first site specific project I had undertaken. This was a project that was supported by the Arts Council England, and took a period of 6 months to develop, which I installed personally with the help of my partner, Ross. I had also closed my label at this point so I was happy to be doing a project like this and I had the time to do it because I wasn’t on the sampling / fashion show / production hamster wheel anymore. Designers were invited by English Heritage to respond with installations rather than garments to the neo-classical architecture of Belsay Hall in Northumberland, in the north of England. Belsay Hall, built in 1807, was an uncompromising and somewhat severe choice of space for showcasing contemporary art and design. I chose to respond, not to the grandeur of the building but, to its hidden history - that of its former employees. My project explored how a designer could excavate traces from the past and use them in a creative format to pose questions about class and working people in pre-war Britain. I started with the oral history archives of English Heritage, listening to interviews with Belsay’s domestic staff recordings from the 1920s and 1930s, and who were actually the relatives of some of the staff working there – the local ties were very strong. I then created a two-room installation named, ‘Foundation’ within the Telephone Room and the Study, that consisted of thickly padded walls using 10 tonnes of fresh white laundry sourced and sponsored from a London recycling center so that the fabrics already had a past life and a patina of age. The fabrics were returned to the recycling plant after the exhibition closed. My use of recycled ‘domestic’ fabrics underlined my focus on the lives of working people rather than the aristocracy. I was trying to pin-point traces of history and the past through the material memories and evocative associations of old cloth. For the sound, I collaborated with the sound artist Scanner (Robin Rimbaud) who mixed fragments of stories told by the original staff and housekeepers. The exhibition attracted over 92,000 public visitors which was impressive for an exhibition which was 25 miles outside of Newcastle and not focused in London.

Which other exhibitions that you haven’t appeared in have found particularly inspiring?

That’s a great question as the ones I have loved have often focused on one designer and not necessarily group shows – but one that comes to mind is ‘Exploding Fashion: From 2D to 3D to 3D Animation’. The exhibition was curated by Alistair O’Neill and was presented at MOMU in Antwerp in 2022. It is described as an exhibition that that explores how pattern-cutting in twentieth century fashion can be understood through the practices of making, unmaking and remaking – it looks at the reverse engineering of pattern cutting through 5 innovative designers, and I loved the intimacy and innovation of the curation and the clarity of the narrative it brilliantly illustrates how we understand the cut of clothing.

Patrick Lee Yow Drafting the pattern of the Balenciaga dress at the Palais Galliera Archiva

Patrick Lee Yow Drafting the pattern of the Balenciaga dress at the Palais Galliera ArchivaCan you tell us about your personal archive, in terms of how you have curated it, what we would find in there, where it’s all kept and also about your encounter with some pesky (dead) mice?

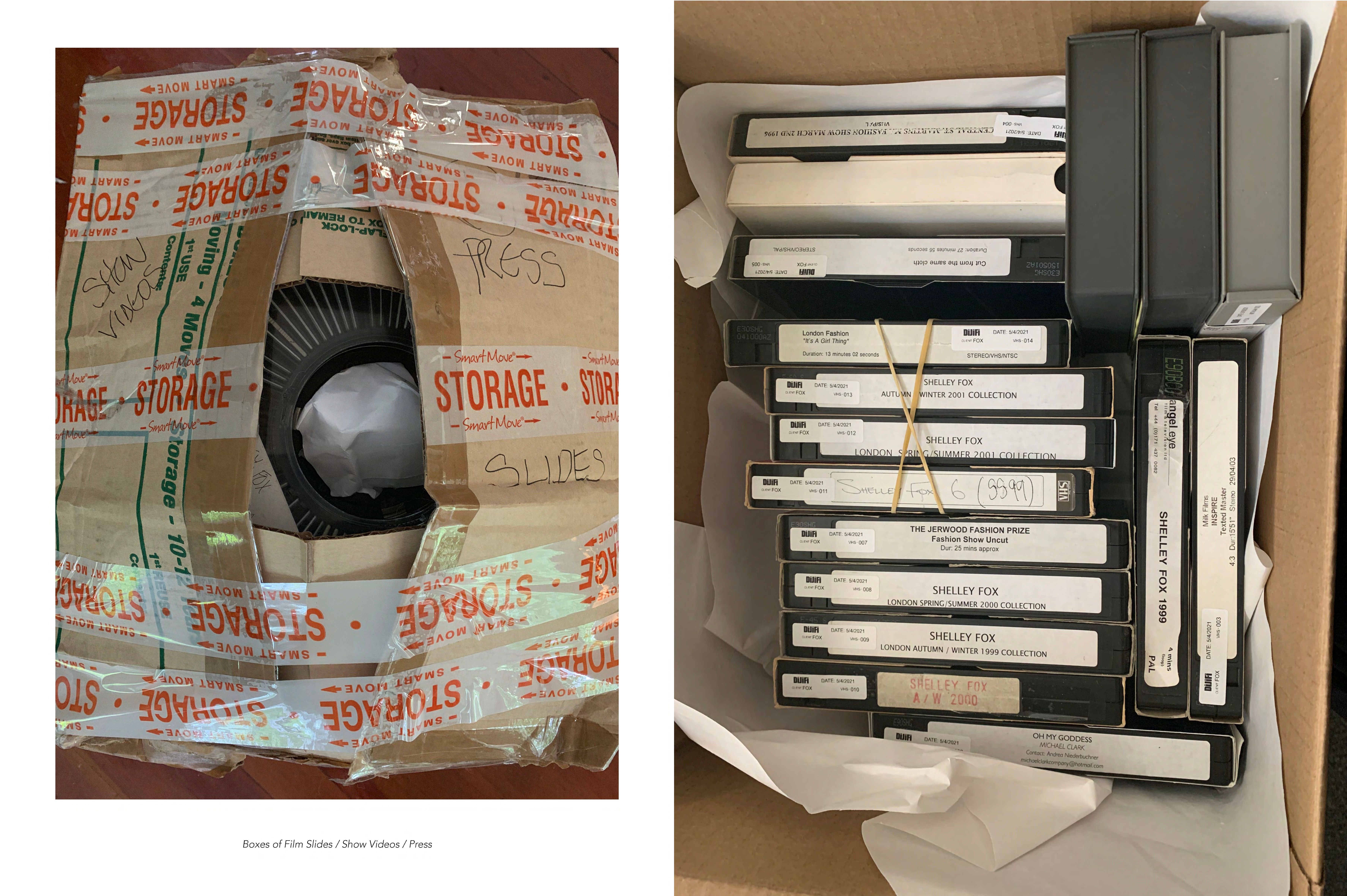

I closed down my studio in 2003 and stopped producing collections for sale. To give a brief overview of the life of this archive; it has travelled extensively and been stored over time in various capacities – old barns in the north of England, my mother’s spare bedroom, my brother’s attic and so on. The garments were boxed and kept at my Mum’s house and each box was numbered with a list of what was in it as curators were still calling my pieces in for exhibitions. The travelling studio / archive got smaller over the years where I cast off elements that I was no longer personally or emotionally attached to – a process of detachment through time. I moved to New York in 2008 and everything was left in the UK until 2011 when we sold our flat in Hackney and Ross, my husband moved over to New York. Select pieces from our apartment in Hackney plus the archive were then moved to a storage space outside Heathrow and stayed there for about 3 years. In 2015 we moved everything over from the UK to a storage space in Brooklyn for another 2 years until we bought our place in the Catskills in Upstate New York. Then we moved everything upstate in late 2018. By this time, I had really forgotten what I had kept. Now that the archive was finally in one place, I immersed myself within it; undertaking a huge sorting process that required me to unpack every box / bag of sorts that I had found and rediscovered; a personal archive that comprises everything from original research references, including various found objects and visual references such as newspaper clippings - some almost 30 years old, xerox copies of other archives, original design developments, various ephemera including analogue runway and exhibition invites, flyers, posters, model fitting Polaroids, hair and make-up test polaroids, 19 clothing collections, original patterns, fabrications, exhibition catalogues, press books (print only / pre-digital), runway shows, VHS video documentaries (from the BBC and The British Council archives – all of which have now been digitised), films, sound and special collections, and random stuff like a RSPCA Dog Coat project for London Fashion Week... I borrowed the studio next doors dog for the fittings of which I still have the polaroids.

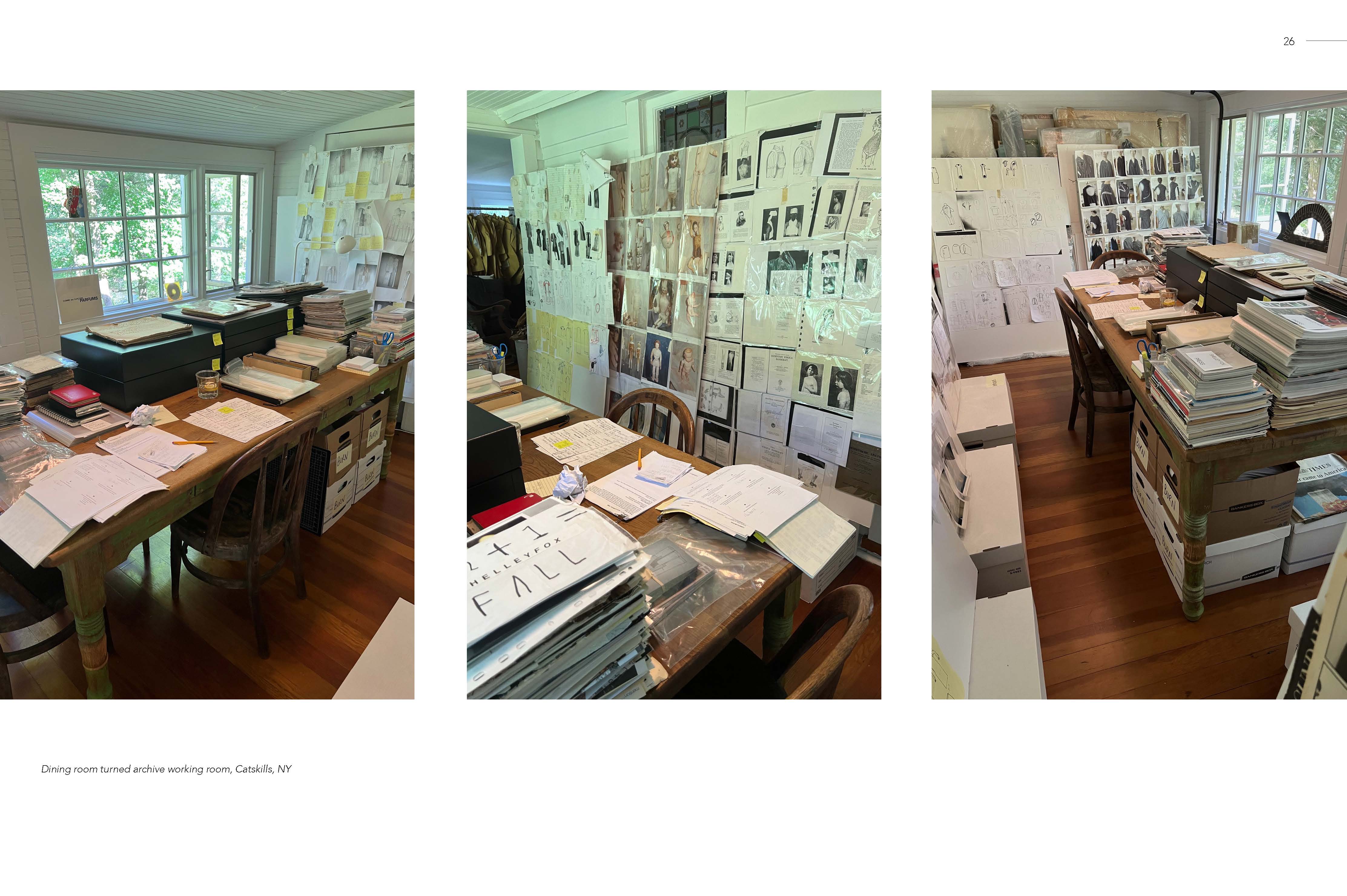

Dining room turned archive working room, Catskills, NY

Dining room turned archive working room, Catskills, NY Boxes of Film Slides / Show Videos / Press

Boxes of Film Slides / Show Videos / PressIs an archive more important for documenting the past or determining the future?

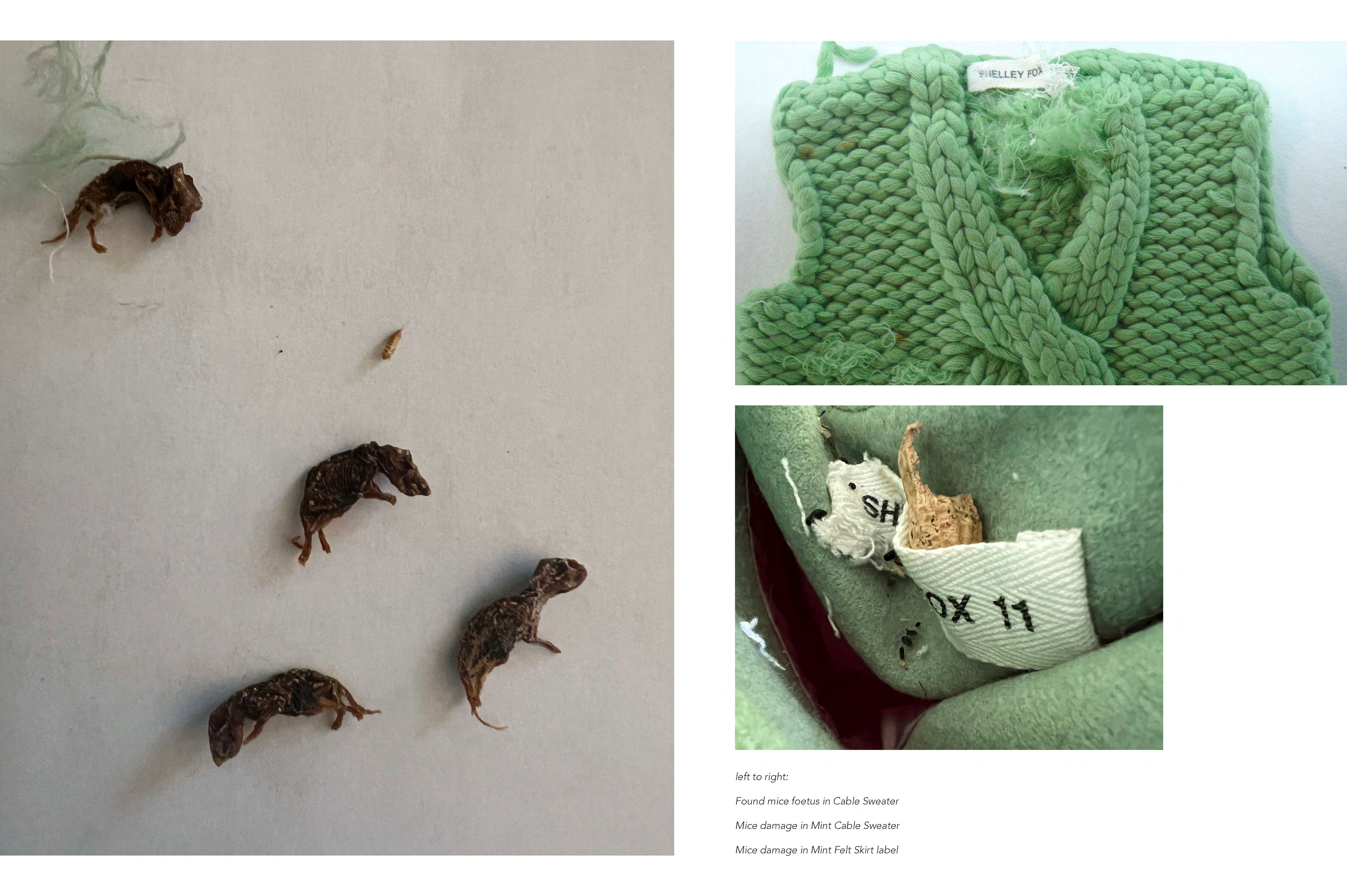

The notion of baggage following you or that you carry around started to come into play particularly when I unpacked two boxes that had been left unintentionally on the lawn over a period of months and weathers – I’d become tired of stored boxes and their overbearing dilemma of what to do with them, so these two boxes in the scheme of things didn’t seem like a big deal. Eventually upon opening them I discovered more clothing patterns and so in that moment I decided to get rid of them – why am I keeping them? What's their relevance to me now? It was a spur of the moment decision – baggage to be finally got rid of and I proceeded to load them all into the car for the recycling plant to take care of only to be persuaded by Ross to take them all back out the car and save them, which I did. Upon closer inspection of these particular patterns, I developed a completely different perspective of them; the beauty of the disintegrated patterns occurred due to unintentional collaborators; the mice and extreme elements of upstate New York weather over a period of time. It has rendered the patterns useless for the purpose of garment construction, but each pattern has become a new version of itself by its ruination, prompting new questions around its next existence. During my sabbatical I finally had the time to go through a linen cupboard where I found a hand knitted cable sweater where baby mice had been born – they were tiny dried dead mice fetuses but the sweater had been used as a nest.

There are elements that intrigue me most about the archive; the starting points of projects that went on to exist in the world in many various guises: clothing, performance, installations, films and exhibitions. Having examined many of the original drawings, collages, documents and facsimiles gleaned from archives and research collections, I see them having new beginnings again - time has allowed for a different perspective. I never anticipated another life for the archive as I just compartmentalised it as a distant memory: boxes of stuff in various stages of transit. Presently I see the archive as a new spring board for prospective collaborators to respond to and work with because the breadth of research themes and references could quite easily be interpreted as they have no relation to fashion as such which I feel offers an open canvas. I am working on a book of the archive bringing all of this process together but I need to physically build it out myself so that I can make sense of it rather than hand it over to someone at this point but it’s taken awhile to realise this.

Left to right: Found mice foetus in Cable Sweater, Mice damage in Mint Cable Sweater, Mice damage in Mint Felt Skirt

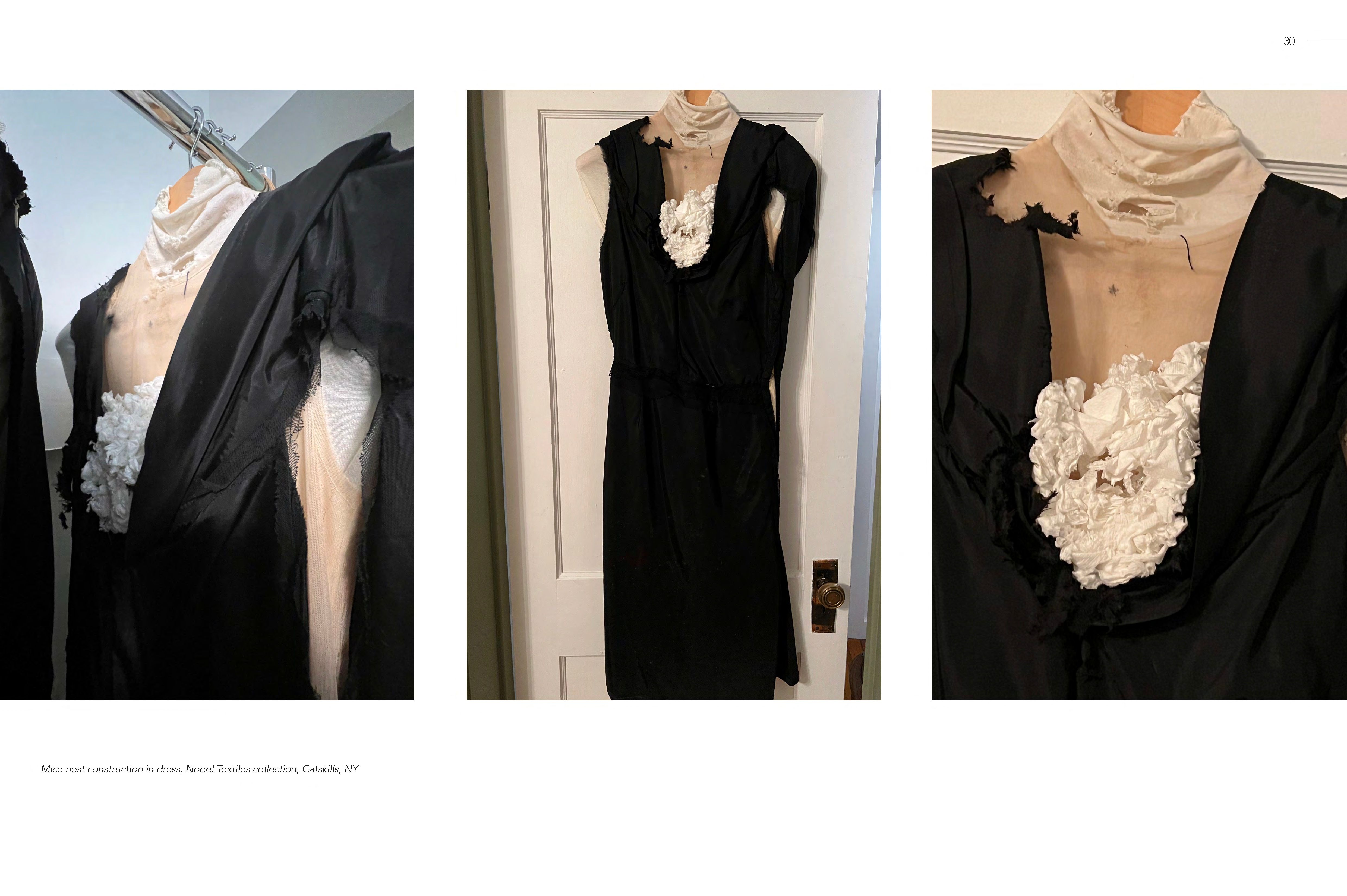

Left to right: Found mice foetus in Cable Sweater, Mice damage in Mint Cable Sweater, Mice damage in Mint Felt Skirt Mice nest construction in dress, Nobel Textiles collection, Catskills, NY

Mice nest construction in dress, Nobel Textiles collection, Catskills, NYHave you encountered many other archives? If so, which ones have impressed you the most and did you encounter any dead animals in them?

When I first moved to New York in 2008, I began writing the MFA Fashion Design & Society program that I founded and directed. As part of this process, I wanted to curate an exhibition on Workwear. I decided to contact the Stanley Burns Archive in Manhattan. I just called Stanley and asked him if he had any images around Workwear. It’s hilarious really because his archive was so overwhelming – he has over 1 million photographs – some very rare tintypes and daguerreotypes – some are in bank vaults now as they are so rare and many around the American Civil War. Over a long afternoon of tea and cake in his townhouse he told me all the stories of how he collected them from flea markets in New York in the 1970s when no one was really interested at looking at them – he collected them because he loved them and knew they were important historical artefacts.

In 2022 when I finally took a sabbatical and was really delving into my archive someone told me about an exhibition of Nick Cave’s archive called ‘Stranger Than Kindness’ which was essentially his entire life and his working process on display. I decided to drive to Montreal from the upstate NY house which is basically a straight line north to Canada. It was amazing to see all his personal effects starting with his early childhood days to The Birthday Party, The Bad Seeds and his entire working process. It was very open. You could sit in his chair in front of his desk with all his song writing and typewriter. It was an amazing trip to see a very personal archive.

You’re currently the Donna Karan Professor of Design at Parsons in NYC, can you tell us what that entails and how you got the gig?

Following a global search, I was hired by Parsons School of Design and relocated to New York City in 2008 to undertake a newly created position. The inaugural Donna Karan Professor of Fashion and my role as the founding Director of the MFA Fashion Design & Society (MAFDS) program was made possible through an endowment made by Donna Karan personally to the University. I was hired as a Full Professor on an expedited tenure track where I was awarded Tenure in 2012. To better understand why this role was created it was important to understand the paradigm shift that was needed within the US fashion education system. The MFA FDS program has had a wide and measurable impact in the field and this program changed the way fashion is perceived in the US from a global perspective. My main role at that point was to write, develop, promote and recruit for the new MAFDS program which launched in Fall 2010. My own ideas around fashion thinking were critical to how the whole program was curated and ultimately how I hired creative talent; filmmakers, photographers, artists, choreographers, curators, creative entrepreneurs as well as academics working within the realm of fashion. I still hold the title but I left the MFA FDS program, the School of Fashion and moved to the School of Art and Design History and Theory in 2023.

How do fashion students in the US compare to the ones in the UK?

Essentially, it’s not so much the students per se but more to do with the teaching philosophy in each country or college and who teaches them. I say this because fashion education recruitment has become so global everywhere. To give some perspective, there were only 2 international students in my entire year when I was an MA student at CSM from 1994-1996, otherwise they were all British. The cost of education has become central to how education has been impacted across the board - it’s really hard for kids with talent from working class backgrounds to enter the system because of the fear of the debt but also, and I said this over 20 years ago at a conference – there are just too many fashion schools and some just not up to scratch and some students just don’t really know why there are there.

How stylish is New York these days and where do you find the most inspiring outfits?

This is a very personal opinion I suppose but I am so over the ‘pilates / gym’ look which is prevalent everywhere and just keeps going. But the when I am walking around the streets it’s often the odd but interesting person who is completely at home in their own style – for example a guy was walking down my street in Brooklyn Heights – cowboy hat, plaid shirt and fitted Wrangler jeans with a great belt – he was so precisely put together in a cool way and really owned it – I just kept looking at him – even the way he walked – he was brilliant – he was in his early 60s maybe.

Who or what do you think epitomises British style?

I think British style is so rich and contradictory – we are a funny small island of contradictions and mixed cultures and class plays a huge part even if quietly – when I had my first studio off Brick lane in the mid 90s I used to love seeing the older Bangladeshi guys with their traditional dress worn with a tailored jacket and Nike trainers – again it looked so smooth and real – the mixture of everything worked – tradition from different cultures mixed up with street looked so naturally cool to me.

Who is your number one style icon?

It’s hard to have a number one, but both Don McCullin and Bill Cunningham immediately come to mind... curious, intelligent, talented and very elegant and appear somewhat very humble. They both record human nature in very different ways but let their work speak first.